A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Thursday, March 31, 2016

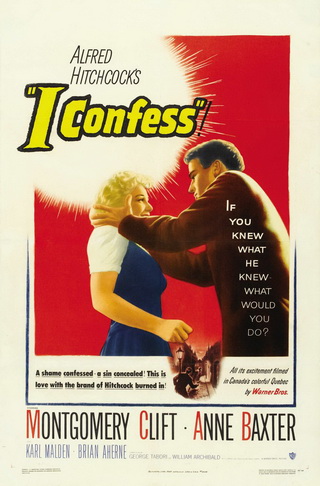

I Confess (Alfred Hitchcock, 1953)

I Confess is generally recognized as lesser Hitchcock, even though it has a powerhouse cast: Montgomery Clift, Anne Baxter, and Karl Malden. It also has the extraordinary black-and-white cinematography of Robert Burks, making the most of its location filming in Québec. Add to that a provocative setup -- a priest learns the identity of a murderer in confession but is unable to reveal it even when he is put on trial for the murder -- and it's surprising that anything went wrong. I think part of the reason for the film's weakness may go back to the director's often-quoted remark that actors are cattle. This is not the place to discuss whether Hitchcock actually said that, which has been done elsewhere, but the phrase has so often been associated with him that it reveals something about his relationship with actors. It's clear from Hitchcock's recasting of certain actors -- Cary Grant, James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Ingrid Bergman -- that he was most comfortable directing those he could trust. And Clift's stiffness and Baxter's mannered overacting suggest that Hitchcock felt no particular rapport with them. But I Confess also played directly into the hands of the censors: The Production Code was administered by Joseph Breen, a devout Catholic layman, and routinely forbade any material that reflected badly on the clergy. In the play by Paul Anthelme and the first version of the screenplay by George Tabori, the priest (Clift) and Ruth Grandfort (Baxter) have had a child together, and the murdered man (Ovila Légaré) is blackmailing them. Moreover, because he is prohibited from revealing what was told him in the confessional and naming the real murderer (O.E. Hasse), the priest is convicted and executed. Warner Bros., knowing how the Breen office would react, insisted that the screenplay be changed, and when Tabori refused, it was rewritten by William Archibald. The result is something of a muddle. Why, for example, is the murderer so scrupulous about confessing to the priest when he later has no hesitation perjuring himself in court and then attempting to kill the priest? No Hitchcock film is unwatchable, but this one shows no one, except Burks, at their best.

Links:

Alfred Hitchcock,

Anne Baxter,

George Tabori,

I Confess,

Karl Malden,

Montgomery Clift,

O.E. Hasse,

Ovila Légaré,

Robert Burks,

William Archibald

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)